As painful as existence is, we[1] cannot really recommend opiates. We had the PSH Research Team look into the subject, and while they recommend them highly, their subsequent decline in correspondence is imperfect from an editorial prospective. Indeed, opioids are probably the most discussed public health issue in America[2]. This has left policymakers struggling with what to do. One thing they have done is expanded the use of Naloxone, a drug which can counteract the effect of a deadly overdose. These laws have undoubtedly saved many lives.

Undoubtedly, unless you ask a couple of economists, Jennifer L. Doleac and Anita Mukherjee, who recently dropped a new working paper onto twitter. The paper claimed that the expansion of laws that make it easier to acquire and use the anti-opioid drug Naloxone, did not reduce fatalities, instead it increased opioid use and increased other crimes.

There was an instantaneous firestorm of debate[3] on twitter. Responses were varied: some folks went on about ‘correlation is not causation’ one commenter called it ‘irredeemably evil’, many praised it, some suspected the reaction might have been different, if authors had not both been woman (a rarity in econ papers).

Here at PSHGHQ, we like it.

We think.

Moral Hazard

The full title of the paper is “The Moral Hazard of Lifesaving Innovations: Naloxone Access, Opioid Abuse, and Crime”. Moral Hazard is an economics term, meaning that: as the costs associated with a dangerous activity decline people will be more inclined to participate in that dangerous activity. This is especially notable in insurance where people who are insured are more inclined to take risks than those who are not.

In this instance, the risk is death from overdose and the insurance is the Naloxone. Someone who is overdosing, is almost certainly going to have a better chance of surviving if there is Naloxone around. By the same measure, having laws that allow easier access to Naloxone should reduce the risk of death from overdose, all else equal.

It seems entirely possible that opioid users change their behavior in response to risks. If you have difficulty imagining someone in the throws of addiction carefully weighing the costs and benefits, think of someone who is just starting out, or considering just starting out, as an opioid user. If all opioids presented no risk of death by overdose, but were otherwise identical to the current crop, no one would be surprised if opioid use increased. Even if opiates merely had less of a danger of overdose there would likely be an increase in the number of users.

A Question of Magnitude

This is a question of magnitude. Which is greater:

The number of people whose lives are saved by prevalent Naloxone[4]

or

the people who start or continue using opioids, who otherwise wouldn’t, who eventually fatally overdose.

Both effects almost certainly exist, it’s just a question of which one is larger. Most people, the contributors to PSH and the authors of this study likely included, would presume that the life saving impact dominates.

Still, it’s worth checking.

Intent to Treat

A note, prior to checking, this is not a study on how people react when Naloxone is available, this is a study one how people react when laws that attempt to make Naloxone easier to acquire are passed. These laws might provide legal immunity to prescribers of Naloxone, laypersons who administer the drug, or laws that allow the purchase of Naloxone without a prescription from the doctor. If the laws don’t work as intended, no one gets Naloxone, the measured impact should be closer to zero.

Causation is not Correlation

Essential to this study is that permissive naloxone laws were rolled out in different states at different times.

To properly test the impact of these laws, laws would have to be randomly assigned to different states. Of course, states don’t randomly assign their laws. It is likely that states with worse opioid problems would adopt these laws sooner than other states. If one were to just measure ‘states with naloxone laws vs. states with no naloxone laws, and saw that opioid deaths were higher in the states that did have these laws, that could easily be because those laws had more significant opioid problems in the first place-which is why they passed the laws.

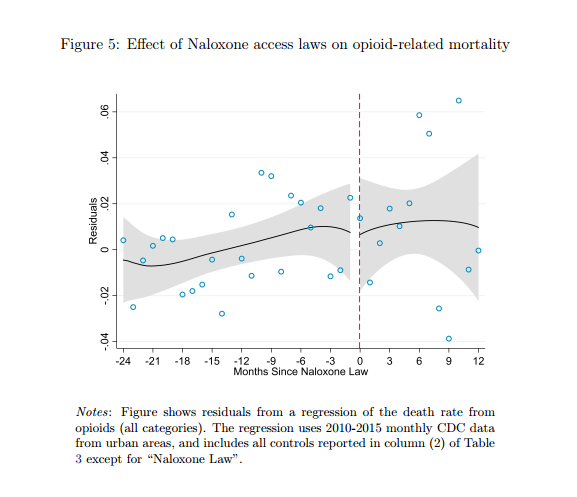

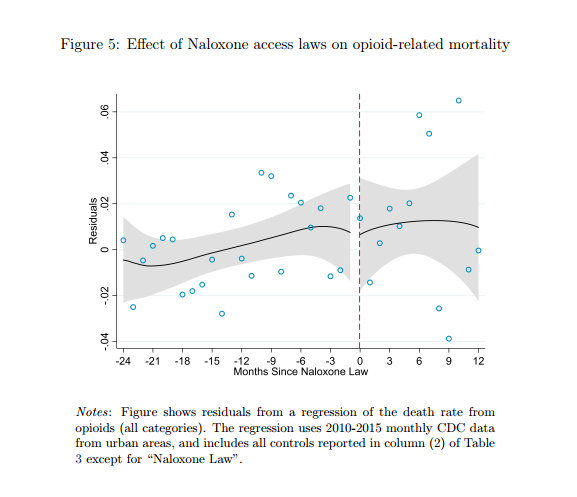

The study controls for preexisting levels in opioid fatalities between states, which should remove this concern. It also controls for national fluctuations in opioid deaths, which should control for things like a rise in opioid use impacting the nation as a whole. The model also controls for trends in opioid deaths in each state.

It is still possible to draw a pure correlation story but it does get awkward. If one wanted to say, claim the results were driven by the increased prevalence of fentanyl. The change in fentanyl would have to coincide with the timing of the laws. Even if this was the intent of policymakers, it would require a level of foresight not present in the typical state legislature.

So, if the results are driven by some underlying variable, it isn’t obvious what it is. In short, we have some confidence in the results, which show essentially no change in opioid-fatalities.

However, the overall trend masks some interesting regional variation.

While Opioid related mortality did not change overall, it did fall in the West. In the Midwest, the opposite happened. This is peculiar, as naloxone is equally effective regardless of where it is administered. One possibility is that Naloxone only actually saves lives if there are also treatment facilities available. There is evidence that counties with more treatment facilities, saw a decline in fatalities, but it is difficult to say for sure. This story certainly makes intuitive sense, after all Naloxone might save someone’s life in the immediate term, it doesn’t really do anything to make it easier to stop using.

Working Paper

This paper does have some flaws. While it focuses on an increase in crime following naloxone, the authors don’t mention the obvious welfare benefit that comes with being revived by Naloxone. Even if a user later fatality overdoses (and mortality does not decline) surely the additional time alive is a benefit.

A potentially bigger flaw has to do with the variables being studied. The different types of laws (listed above) seem fundamentally different. We would expect, based on no evidence-we literally haven’t even bothered to google it, that laws making naloxone legal to purchase without a prescription would have a larger impact than the other types of laws. On Twitter, Mukherjee, responds to a question on this, explaining that it was difficult to evaluate the laws separately, as different ones were often passed together.

There is also the issue, of other, contradictory research. A similar study, which no one at PSHGHQ bothered to read, found opposite results. That study used less detailed data (state and year) as opposed to the more detailed data used by Doleac and Mukherjee.

In our view, the policy message from this paper is less the potential moral hazard story-although we are tempted to buy into that-and more the limited impact that can be achieved by passing of naloxone laws, especially if they are not accompanied by sufficient opportunities for treatment.

One of the most vital jobs that policy researchers have is to check if policies in-fact work as intended, this is perhaps most important when these sorts of policies have widespread or intuitive support. To this end, Doleac and Mukherjee have succeeded. We will be keeping an eye on this debate, and are curious to see how it turns out, assuming we live that long.

Related PARTYSHEEPHATS posts

How Much Consumer Surplus Does Uber Generate?

How should companies that operate private prisons be paid?

Source, References, and Related Reading

The paper this article is about

Rees et al. 2017. Also on Naloxone

Video of Naloxone Use. [Warning, contains distributing local news voiceovers].

[1] Observant readers will notice that some articles for this website are written by “we” and some by “I”. There is no explanation for this.

[2] Maybe not if you count gun violence as a public health issue.

[3] “Debate”

[4] The lifesaving effect might be muted, if opioid users continue to use, and overdose later.