If you ever are at a party, and you stumble into a conversation that is quickly flatlining, you can always attempt to revive it by asking your fellow revelers the following question: “Which unemployment rate do you like the best?”

There are different unemployment rates?

The BLS keeps track of six different unemployment rates. Because the BLS (like most organizations whose names consist entirely of consonants) is not the most creative organization, these are called U-1, through U-6.

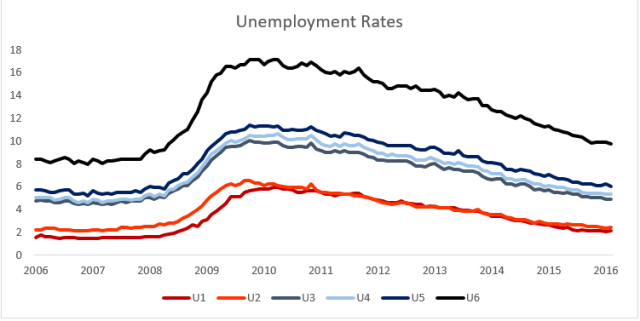

Here is a plot of the six different (seasonally adjusted) rates over the last decade. All of the rates follow each other fairly closely, so If one rate goes down, the others will almost certainly follow the same trend. There is substantial variation in terms of the absolute magnitude, and unemployment seems like an absolute magnitude worth caring about.

We should be interested in the unemployment rate for similar reasons as we are interested in the economy as a whole. However, the unemployment rate is not just an abstract index of the strength of the labor market. It is also supposed to be a meaningful measure in its own right. An unemployment rate of 5% should tell us that 5% of our labor force is unemployed. The different measures of unemployment differentiate themselves by counting different groups of people as unemployed or as looking for work.

The Different Unemployment Rates:

U-1 = Persons unemployed 15 weeks or longer/The Civilian Labor Force.

Seasonally Adjusted Value- Feb 2016 = 2.1 Percent

The Civilian Labor Force

The group of people that gets counted as either employed or unemployed is summed up as the civilian labor force. This is everyone over 16, who is not in prison, or in the military, who is either employed or unemployed. To count as employed one needs to work any amount for pay or profit, to count as unemployed one needs to have not worked but be actively looking for work.

Some of the people who are not counted in the civilian labor force include: full time students, retirees, stay at home parents, and discouraged workers who have given up on finding a job. As of last count the civilian labor force was 158.9 Million, which is about half of the US population.

U-1 is the strictest measure of unemployment. Not only does one have to be unemployed, one has to have been that way for at least 15 weeks. This measure should capture the long term, chronically, or structurally unemployed. This is the group of unemployed people who are unable to find work due to a fundamental disconnect between what they have to offer and what is needed by employers.

U-2 = Job losers and persons who completed temporary jobs/the civilian labor force

Seasonally Adjusted Value in Feb 2016 = 2.4 Percent

While U-2 tends to closely follow U-1 it is calculated in a different way. The BLS breaks down unemployed people into four categories based on what happened in their previous job: Job Losers and persons who completed temporary jobs, Job Leavers, Reentrants, and New Entrants. U-2 counts only people in the first category, Job losers and persons who completed temporary jobs. These are people who have lost their jobs do to being fired or laid off, or people who have finished a temporary job and have not been able to find another one. It does not count people who leave their jobs voluntarily, people who are reentering the labor force after a long absence, or people who are entering the labor force for the first time.

Both U-1 and U-2 are narrow measures of unemployment. They both try to emphasize the most damaging parts of unemployment. U-1 does this by counting only those people who have been unemployed for a significant period of time. U-2 does this by counting those people who recently had jobs, and were forced to leave them.

U-3= Unemployed/Civilian Labor Force

Seasonally Adjusted Value in Feb 2016- 4.9 Percent

Whenever someone in a news report mentions the unemployment rate they are talking about U-3. U-3 is by far and away the most commonly used measure of unemployment in the United States. It is also one of the most straightforward to calculate. It is the number of unemployed people as a percentage of the total number of people in the labor force. Unlike U-1 and U-2, it does not make any further restrictions on which unemployed people to count. Everyone in U-1 and U-2 is also in U-3.

U-4= Unemployed + Discouraged Workers / Civilian Labor Force+ Discouraged Workers

Seasonally Adjusted Value in Feb 2016- 5.3 Percent

To count as part of the labor force, one needs to be working, or actively looking for work sometime in the last four weeks. Looking for employment can be a discouraging and unpleasant process, and some people give up when they cannot find employment. People who have actively looked for work within the last 12 months, but have not looked recently due to economic conditions are counted as discouraged workers. These are people who feel (correctly or incorrectly) that there are no jobs available for them or no jobs that they would qualify for.

U-5= Unemployed + Marginally Attached Workers/ Civilian Labor Force + Marginally Attached Workers

Seasonally Adjusted Value in Feb 2016- 6.0 Percent

Discouraged Workers are a subset of people who are classified as marginally attached to the labor force. Marginally Attached Workers are workers who are available for work, who would like to work, and have sought employment within the last year (but not in the last 4 weeks). Unlike discouraged workers they do not need to have stopped looking for work due to economic conditions. This means that everyone in U-4 is also in U-5.

U-6 = Unemployed+ Discouraged Workers + Part time due to Economic Reasons/Civilian Labor Force + Marginally Attached Workers

Seasonally Adjusted Value in Feb 2016 = 9.7 Percent

The broadest measure is U-6. U-6 includes everyone in U-5 but also counts those people who are working part time due to economic conditions. These are people who are available to work full time, would like to work full time, but can only manage to find a part time job. There are a lot of these people, just under 6 million in Feb 2016, and they bump up the total value of U-6 to 9.7 Percent. Because of its magnitude, U-6 tends to be the indicator of choice for people who would like to point out just how badly the labor market is doing.

Which Unemployment Rate is the Best?

At this point, a boring person would say that trying to figure out which unemployment rate is the best is a little silly. Each rate has its purpose and you should look at different ones (or even better at all of them) in order to get a full sense of the labor market picture. This is true, but there is value in having an indicator you can turn to in almost all cases. Historically this has been U-3.

The Best Unemployment Rate is…

The best unemployment rate is the one that give us the most information about the strength of the labor market, while still being a real measure in its own right. U-1 and U-2 are both too narrow for most purposes. They really are designed to measure a subset of the unemployed and not the total unemployed population. U-3 is good, and has the added advantage of being what we are used to using and talking about. I prefer U-4. Adding in the discouraged workers gives a more accurate indicator of people who would think of themselves as unemployed. These are clearly people who are not working due to economic reasons, which is just the thing the unemployment rate is trying to capture. U-5 takes it a bit too far, everyone marginally attached to the labor force adds in a lot of people in a mess of different situations.

U-6 is interesting. The people who are working part time (especially if it’s just a few hours a week) instead of full time are surely suffering many of the negative effects of unemployment. The problem with U-6 is that it isn’t really an unemployment rate. Once a good chunk of the people in an indicator are employed, even part time for economic reasons, it isn’t really an unemployment rate anymore. While U6 is a good indicator for the health of the labor market, it is not a good unemployment rate.

So that leaves us with U-4. Which wins the official PARTYSHEEPHATS nomination for best unemployment rate. Congratulations U-4! Go do whatever it is economic indicators do to celebrate. Go down or something.

Sources and Further Reading

http://www.bls.gov/lau/stalt.htm

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t15.htm

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf

http://portalseven.com/employment/unemployment_rate_u1.jsp