How Many Airlines Fly to Chicago?

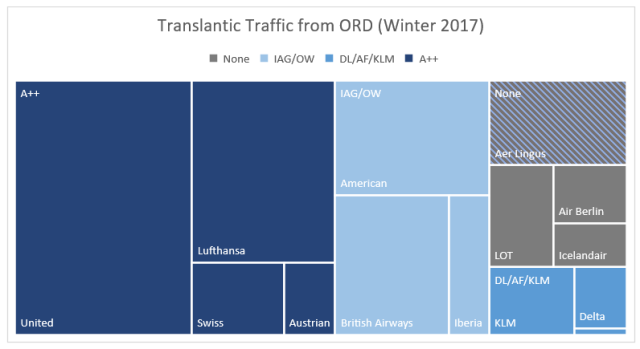

With nearly two dozen carriers to choose from, a passenger wishing to travel from Chicago to Europe would be forgiven[1] if they thought they were spoiled for choice.

A typical July day at O’Hare. Image Source

Chicago O’Hare International airport is the world’s 6th busiest, and nearly every European airline flies there. Connecting options in North America, or Europe[2], mean it is possible to use any of these carriers (with the possible exception of WestJet) to travel from Chicago to every major European city.

International Airline Groups (and the International Airlines Group)

While there are over twenty airlines represented here, there are not twenty companies. Lufthansa is owned by the Lufthansa Group, which also owns Swiss and Austrian (along with Brussels Airways, Germanwings, Eurowings. Edelweiss, and others that don’t fly to Chicago). British Airways, Iberia and Aer Lingus are all owned by International Airways Group. Air France and KLM merged to create the creatively titled Air France-KLM Group[3]. This changes the picture somewhat.

The Dominance of the Joint Ventures

The North Atlantic airline industry is dominated by the Joint Ventures[4] (JV). Each is a subset of the three main airline alliances (Star Alliance, One World, and Sky Team). These groups of airlines have been given antitrust immunity (ATI) by the US and the EU governments, and can coordinate schedules, capacity, and prices on transatlantic routes. The main transatlantic JVs are:

| OneWorld/IAG | A++ | SkyTeam/AFKLM |

| American Airlines | Air Canada | Air France |

| British Airways | Austrian | Alitalia |

| Finnair | Brussels | Delta |

| Iberia | Lufthansa | KLM |

| Swiss | Virgin Atlantic | |

| United |

These airlines cooperate closely, effectively pricing as one unit. There are Swiss, United, Lufthansa, and Air Canada Employees sitting next to each other in the United offices in downtown Chicago.

The JVs dominate transatlantic traffic. They carry 83% of transatlantic traffic out of O’Hare[5]. United and American both have hubs in the Windy City, both are involved in JVs. Every US airline that offers scheduled transatlantic service does so as part of a JV.

Aer Lingus is unaligned but owned by IAG. The unidentified sliver in the bottom right is Air France

It’s not just Chicago, 78% of available seat kilometers (ASK) [6] across the North Atlantic are on one of the JV partners. A 2011 department of Justice paper estimated that 82% of US-EU traffic was on one of the JVs.

The argument against antitrust immunity is straightforward. Competition is good for consumers, it keeps prices low and quality high. Reducing the number of competitors in a market increase the possibility of collusion. Allowing airlines to mutually conspire to set prices and schedules flies[7] in the face of most thinking on competition.

The argument for antitrust immunity is subtler, but it does exist.

The pro consumer argument for eliminating competition

Imagine a world populated by airlines that (much like the contributors to this website) have an abiding mutual hatred and want nothing to do with each other. These airlines don’t even allow interlining[8].

There are things about this arrangement that are nice for consumers. On routes where the airlines compete there is sufficient, and sufficiently fierce, competition, which should keep fares low.

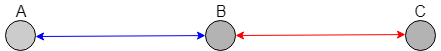

There are also things that are not so nice. Some markets, such as secondary cities, may have limited service, and cities with limited service may be confined to the route network of just one or two carriers. As shown in the illuminating diagram below, a passenger who wants to travel between A and C needs to buy a ticket on Blue Airlines, and then a separate ticket on Air Red. This is likely to be expensive and annoying.

This Illuminating diagram

Double Marginalization

Connecting monopolis is expensive and annoying due to double marginalization, a situation where two monopolies are worse than one. Imagine Blue Airlines and Air Red are monopolists on routes A-B and B-C. Naturally, there are many passengers who would like to travel from A-C or C-A. Being a monopolist, each airline sets its prices at an elevated level. For passengers wanting to travel from A-C, the high fares from A-B discourage passengers from booking tickets to B-C, and high fares from B-C discourage passengers from booking A-B. This means that few people will travel from A-C.

If both routes were run by the same airline, it would have monopoly pricing on A-C, A-B, and B-C. The pricing on A-B and B-C would not change, however the pricing of the single monopolist on A-C would be more accommodating than the two monopolists acting separately. Due to the increase in total passengers, a single monopolist would have greater revenue than the combination of the separate companies.

Everyone, passengers, Blue Airlines, and Air Red, would benefit from a lack of competition.

Degrees of Cooperation

There are other arguments for more integration among carriers. Aside from double marginalization, it might improve the experience for travelers if airlines could share things like airport lounges and frequent flyer programs. Cost sharing and economies of scope, might lower overall costs.

What is less obvious is what degree of cooperation is best. Airlines can (and do) interline without antitrust immunity; they also codeshare, and band together to form airline alliances (Star Alliance, Sky Team, and OneWorld). Even antitrust immunity regimes have variety. Some have had carve outs where the immunity doesn’t apply for certain routes (such as ORD-FRA or ATL-CDG).

In theory, double marginalization is present unless both carriers combine into one. Antitrust immunity seeks to do this without the bother of having a full merger. A key feature of this is metal neutrality, which means that airlines share revenue regardless of whose aircraft a passenger flew on. This differs from traditional interline or codeshare agreements, and is done to keep the airlines from competing for passengers.

Does it work?

Antitrust immunity’s fundamental tradeoff is decreased double marginalization and possible cost savings, vs. the loss of direct competition.

It is clear that the airline alliances are an improvement over less cooperative interlining arrangements. It also seems that the antitrust immune JV’s do successfully eliminate the double marginalization problem, however it is not obvious how much benefit (if any) they provide over an alliance.

There is evidence that more competitors do lead to lower prices, and it seems that both prices and profit margins increased on Atlantic routes relative to domestic and Latin American routes.

Results might be genuinely mixed, depending on where passengers are going. For budget travelers who are traveling between major cities, especially hubs of carriers in the same JV, antitrust immunity is likely harmful. For travelers who are flying from small markets, especially when traveling to other small markets, the antitrust immune joint ventures might well be beneficial.

I remain skeptical of the benefits of antitrust immunity. In a world of increasing market power, any willful increases in concentration should be treated wearily. Any concession of antitrust immunity should be temporary, and should periodically require the reaffirmation of regulators. In this process, the burden of proof should fall on the carriers, to prove what they are doing has been beneficial to consumers.

Open Skies and Foreign Ownership

The US and the EU have an Open-Skies agreement, that allows for any European airline to fly to any US city without additional regulation, and any US carrier to fly to European cities without additional regulatory approval. This opened up previous restricted markets such as London’s Heathrow airport. Regulators often invoke the benefits of Open Skies in defense of the idea that contestability will keep competition robust and fares low. This might be happening. Non JV transatlantic carriers have increased frequencies by 155% since 1998. Although it isn’t obvious what they might have done in the absence of the joint ventures.

There are other ways that governments restrict airline competition. Most importantly are the rules that restrict foreign ownership, and foreign competition. If regulators wanted to truly encourage competition, they would remove these barriers. It is unlikely to happen soon.

Editor’s note: The author of this article formally, and briefly, worked at United Airlines, doing atlantic pricing.

Related Posts

Are Monopolies Ruining Everything?

Why is Flying in Canada so Expensive?

Sources, References, and Further Reading

Volodymyr Bilotkach and Kai Hüschelrath

CareerAnna-double marginalization

mruniversity-double-marginalization-problem

Interline and code-share agreements by Arpad Szakal

[1] But not by us. We do not forgive.

[2] Middle Eastern, South and Central American, and Asian Carriers are also present, but using them to get to Europe is awkward.

[3] Some of the non-JV carries have substantial overlap with other carriers, (recently bankrupt) Italian carrier Alitalia and, (recently bankrupt), German carrier Air Berlin are both 49% owned by (not yet bankrupt) Etihad. Delta owns 49% of Virgin Atlantic (who is a member of its Atlantic Joint venture that does not fly to Chicago).

[4] There are also non-Atlantic JV’s, for example United and ANA have one over the pacific.

[5] My data based on BTS market data for 2017. This almost certainly underestimates it, as the data only includes transatlantic passengers who fly directly out of Chicago, as opposed to those that originate in Chicago and connect to a transatlantic flight in another gateway such as New York, Atlanta, or Toronto.

[6] ASK or ASM is the amount of available of seats * the number of miles/kilometers they will fly. It is a standard measure of airline capacity.

[7] Heh.

[8] Interlining is the process where airlines mutually agree on an arrangement that allows passengers to travel using multiple airlines. One airline, usually the one that starts the journey, will be the ticketed carrier, with other segments operated by a separate airline. The first airline, reimburses the second for their role in transporting the passenger.

Shouldn’t interlining barriers go away in a competitive environment? It seems as if the case for antitrust immunity goes like this: one larger monopoly is better than two smaller ones. But that seems very weak when the alternative is competition on all the routes, including the routes run by the two monopolies.

Another alternative, not discussed, is government rate-setting. I know it’s not within your topic but . . .

LikeLike

I think you are correct that perfect competition would have pretty minimal or nonexistent interline markup. If everyone flew everywhere the main motivation for interlining (completing otherwise uncompletable itineraries) would vanish.

It would be great if there were competition on all routes, but i’m not sure this the alternative. Especially for transatlantic traffic where there are carriers with their own network on each side of the pond, with some limited overlap in the middle. These never compete with each other on most domestic/intra-europe routes (foreign carriers are prohibited from carrying domestic traffic), so there will always be a relatively few options (outside of major gateways) on either end.

LikeLike