(This is part 2 of an unintentional series on expensive Canadian things. Part 1 is here)

Flying within Canada is very expensive. It was ranked 70th of 75 in Kiwi.coms Aviation price index which gives the average cost to fly 100km.

On a couple random dates in October the cheapest flight I could find from Vancouver to Montreal was 450$ US, or about $600 Canadian. Partially, this is an expensive ticket because Canada is a big place, but a flight to Montreal out of Seattle on the same dates was $100 (USD) cheaper. This is true, even with the US ticket having more taxes and fees. Having to pay both US and Canadian fees, plus immigration fees, adds up.

While it’s true that Canadian Airports charge high landing fees to airlines. Mostly, it’s an expensive ticket because there are only two choices on airlines: Air Canada, and WestJet.

Duopoly

Air Canada and WestJet are basically the only choices when flying domestically within Canada. Porter serves a few eastern cities, and there are airlines with awesome names like Air North, and Bearskin, which will take you to places that are even colder than Montreal or Toronto. There are also a few other Canadian airlines who mostly fly to places that are not Canada such as Air Transat, and Sunwing.

The main reason, the Seattle-Montreal Itinerary is so much cheaper is because along with Air Canada, Delta, United, and American will also sell you tickets. It’s the old recipe: more firms, more competition, lower prices.

Freedoms of the Air

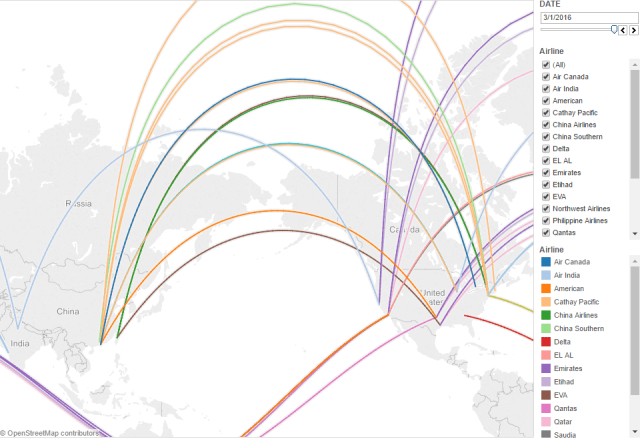

With so much traffic just south of the boarder, and all major Canadian airports served by multiple US carriers, one might imagine passengers could simply book a ticket from Vancouver to Montreal through an intermediate US stop. For example, YVR-ORD-YUL. This would allow US Carriers to compete with Canadian ones, without flying directly from Canadian airport to Canadian Airport. Of course, there would be the hassle and fees involved with customs, but since most Canadian Airports have US pre-Clearance facilities, you could connect in a US airport like any domestic US passenger.

This is an impossibility. Flight searches will not display any options involving connecting in the United States. The reason for this has to do with a set of rules with the decidedly romantic name of ‘The Freedoms of the Air.’ These are negotiated between countries and govern what foreign carriers are allowed to do. Almost nowhere in the world (except for the EU) is a foreign airline allowed to operate domestic flights within a country that does not share its flag. Not only can US carriers not fly from Vancouver to Montreal directly, they cannot even sell tickets on this route, regardless of the actual path the aircraft takes. The same is also true if you start and end in the US, you cannot go from one US destination to another and connect in Canada.

Room for more?

If the cause of expensive fares is limited competition, is there room for more competition to bring them down?

In markets where there is too little competition firms typically have higher profits. High profits are not something the airline industry has been historically known for and Canadian Airlines are no exception.

2015 was a good year for pretty much every Airline[1], but Air Canada has typically struggled to make money. WestJet has been better, but it is not a market that new companies are leaping to enter. Furthermore, barriers to entry and large capital costs (planes aren’t cheap) have always made it hard to start a new airline. Canadian airline startups may be further hampered by requirements that cap foreign investment in airlines at 25%.

Maybe the problem isn’t the number of firms but rather their type. Ultra-low cost carriers (ULCCs) have been successful all around the world. Ryanair, Spirit, AirAsia, Norwegian, and company have all managed to make money by squeezing more people into planes and then charging them for everything. Canada has no low cost carriers. Until now. Startup carrier NewLeaf[2] recently started offering flights out of Winnipeg to secondary cities across Canada such as Kelowna and Hamilton. NewLeaf has not gotten off to a strong start, suspending some flights due to minimal demand.

As domestic competition is likely to remain limited, Canadian travelers will likely be stuck with expensive tickets for a while. Unless Canada wants to give 8th or 9th freedom rights to US Carriers. Doing so would probably be bad for the Canadian airline industry, it might not be so bad for Canadians though.

Article Seven

It won’t happen. Even if the Canadian government were interested in doing this, which they arn’t, it’s not certain it would be legal. The issue comes from the international rules concerning cabotage established at the 1944 Chicago Convention. Cabotage is when a foreign carrier transports people or goods within a country, same as the 8th and 9th freedoms of the air. One of the rules (article seven) is that countries cannot give cabotage rights exclusively to another country or airline[3]. What this means is not entirely clear. The most likely interpretation of this is that the US and Canada could not make an agreement with Canada that only US airlines can conduct cabotage in Canada. An alternative interpretation could imply that Canada may not offer cabotage to US carriers without also offering it to the airlines of other countries. At present, the only country that currently allows foreign cabotage is Chile. It seems unlikely that Canada will be the second.

Unless NewLeaf or another Low Cost Carrier is successfully able to come on the scene, it seems that Canadians will have to continue to fly on Air Canada and WestJet, and that domestic fares will remain high.

Sources, References, and Further Reading.

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/newleaf-puts-brakes-on-winnipeg-flights1.3766914

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freedoms_of_the_air

http://www.icao.int/publications/Documents/7300_9ed.pdf

[1] Also, the only year in which I worked for one. Not a coincidence.

[2] As a virtual New Leaf owns no airplanes, but sells tickets onto flights run and operated by other airlines such as Flair Air. Most of the regional US airlines also function in a similar manner.

[3] The actual text is: “…Each contracting State undertakes not to enter into any arrangements which specifically grant any such privilege on an exclusive basis to any other State or an airline of any other State, and not to obtain any such exclusive privilege from any other State.”